Care for Your Mind acknowledges and appreciates the collaboration of the National Network of Depression Centers in developing this series.

I Had Postpartum Depression and the System Failed Me

Jamie Belsito

After the births of each of my two daughters, I suffered from postpartum depression (PPD), OCD, anxiety, and intrusive thoughts. Both were terrifying experiences. There were times I wanted to go to sleep and never wake up, times I experienced visions of stabbing myself with sharp objects. My experiences made no sense to me, as I was joyful about both of my pregnancies and the births of my daughters.

During what was to be the most wonderful time of my life, instead, I felt alone and completely confused. I didn’t know where to turn, and even when I reached out for help, the response from the medical community was inadequate.

The health care system was ill prepared to support me and my family, leaving me floundering to find mental health help on my own, while dealing with the pressures of being a new mother. This struggle inspired me to want to change the state of perinatal mental health care in this country, and now I advocate for the issue in my home state of Massachusetts and nationally.

Research has shown there are simple, cost-effective ways to offer support and care to pregnant women and moms. It’s been done in Massachusetts, and we have the potential to see similar efforts roll out nationally. It’s time to destigmatize PPD and stand together to support moms.

My Story

The first time I experienced PPD, I was blindsided. After suffering a miscarriage at 34, I became pregnant again at 35. My first daughter was delivered by emergency cesarean section after 27 hours of labor. The delivering doctor’s demeanor made me feel like I was responsible for not being able to birth my child. The experience made me feel deflated and anxious.

My daughter was a challenge—she suffered from jaundice, was allergic to dairy and soy, and had acid reflux. She was so sick, and all she wanted to do was self-soothe through crying and nursing.

Physically exhausted, I became very depressed and was riddled with anxiety and insomnia. I remember thinking, I’ve done my job. I’ve brought this beautiful child into this world—I can just close my eyes and go to sleep and never wake up; she’ll be fine.

After I poured my heart out to my obstetrician (OB) at my six-week visit, she suggested I might have PPD. I was relieved that the condition had a name—at least it was something I could label. But her only solution was to write me a prescription. I received no follow-up, no support, and no care coordination.

When the prescription wasn’t enough, I did some research and tracked down a support group. No one showed up to the meeting, and eventually, I found my way to the hospital social worker’s office. There, they handed me a pile of paper—contact information for therapists.

I was at the bottom of the ocean, and it felt like they’d tossed me an anchor. In the midst of depression and the stress of new motherhood, I was expected to track down my own care—a task that felt insurmountable. But I’m a swimmer—I don’t sink, and I was determined to find a way to help myself.

It took me an excruciating eight or nine weeks to find a therapist—the hardest time of my life. Once I finally received the treatment and support I needed, slowly but surely I started feeling normal again.

When my second daughter was born, the PPD resurfaced. This time, I was overwhelmed with compulsive anxiety, anger, and fear. I didn’t realize there was a spectrum of symptoms within PPD, so I wasn’t sure what was happening. It ended up being just as difficult to get care despite the fact that my OB knew about my history.

Eventually, after countless phone calls, appointment delays, and a desperate, last-ditch plea for help, I was able to receive treatment and start feeling like myself again.

What Went Wrong?

Before Massachusetts introduced MCPAP for Moms (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project for Moms), it was extremely challenging to find practitioners who were properly trained to treat PPD. Despite the fact that Boston is one of the best medical cities in the nation, it was next to impossible for patients who lived outside the city center (like me, 20 miles north) to access treatment—a fact that spoke volumes about the state of women’s mental health care.

The real problem lay in a lack of provider training and resources. OBs and pediatricians didn’t feel qualified to provide behavioral health care, were without a referral network, and had no systematic approach in place to handle the issue. Basically, even if they identified PPD, they had no idea what to do. That’s why I, along with so many other women, was left without care.

Changing Care in Massachusetts

Things have changed since I delivered my first daughter in 2010, and even more so since my second in 2013. Now, MCPAP for Moms ensures that every doctor statewide has access to a program that provides support, referrals, and medical advice for maternal mental health treatment. An upcoming post in this series will go into more detail about MCPAP, discussing how it started, its structure, and what lies ahead.

I’m so grateful we’ve seen this kind of progress, and I look forward to the day when moms everywhere have available care.

Normalizing the Issue

So what’s the answer to fixing our broken system? As an advocate, I think normalizing the issue is a huge piece of the puzzle. Women need to know PPD is an extremely common complication of pregnancy. Just like gestational diabetes, mental health needs to be a part of the conversation, starting with the first ultrasound. If it were part and parcel of the overall experience, it wouldn’t seem so daunting.

To help change public perception, I’d love to see a national education and PR campaign. I think a large-scale destigmatization effort could make a world of difference. Why not create posters talking about how common PPD is and what to look for? A hotline? Public service announcements? Moms need to know PPD is normal and that there are places to turn. In Massachusetts, with MCPAP for Moms and community support groups such as MotherWoman and Postpartum Support International(PSI), care is now much easier to obtain. Elsewhere in the country, groups like PSI offer phone and online support and resources for moms in need.

Women often suffer in silence. We’re hesitant to talk about our mental health, in part because we’re afraid someone might take our children away or label us unfit mothers. There’s still a powerful stigma attached to these issues.

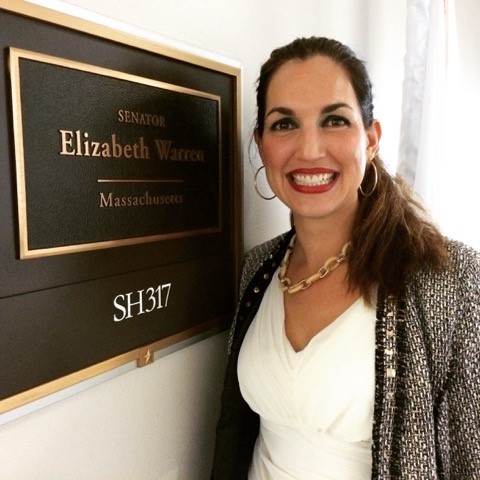

Advocacy efforts are helping to push this topic to the forefront and make it a part of the common conversation. As part of my role as National Advocacy Chair at the National Coalition for Maternal Mental Health (NCMMH), I speak at national conferences, meet with legislators, and tell my story as often as possible. I believe in the power of candor; the more we each admit to our struggles, the more other women in need will feel heard and supported, and eventually, this preposterous stigma will disappear.

I’ve discussed my story and the importance of advocacy as this cause gains greater momentum. As part of my message, I frequently talk about the fact that doctors need support and resources to offer better care. The next post in this series will revolve around this issue, covering what’s been lacking for providers and how better care models are being developed.

No woman should have to suffer like I did. Together, we can change the system and make sure every mom has access to care so she and her baby are happy, healthy, and safe. Please read next week’s post: Why Doctors Can’t Treat Their Patients: Barriers to Mental Health Care for Obstetricians and Pediatricians. Subscribe to CFYM to so that you automatically receive each week’s post in this series every Tuesday.

Your Turn

- How has perinatal depression affected you or someone you know?

- What do you think is important as we address maternal mental health?

- What have you experienced or heard of that has been effective in identifying and treating postpartum depression?

BIO

Jamie Belsito was challenged with unexpected mental health issues, termed Postpartum Depression [PPD], during and post pregnancies with both of her children. It was during this time that Jamie found out about the difficulties of finding quality mental health care to address PPD, as well as lack of communication around the issue of PPD at the OB/GYN’s office, primary health care office and at the pediatrics offices. In the fall of 2013, she became a member of the North Shore Postpartum Taskforce [NSPPDT, founded out of the Birth 2 3 Center in Ipswich, with community based local groups and clinicians who support Mom’s and families working through the temporary and treatable conditions of PPD. In partnership with Senator Joan Lovely, Senator Bruce Tarr, Representative Brad Hill, MCPAP for Mom’s and the Special Commission for PPD, Jamie began to help educate the Statehouse and stakeholders on PPD, gaps in the system and what Mom’s may need to get better. Jaimie has partnered with grassroots groups and local legislators to help ensure passage of funding for MCPAP for Mom’s, PPD pilot program and implementation of universal PPD screening for Mom’s in the Commonwealth, commencing in 2016.

Connect With Us